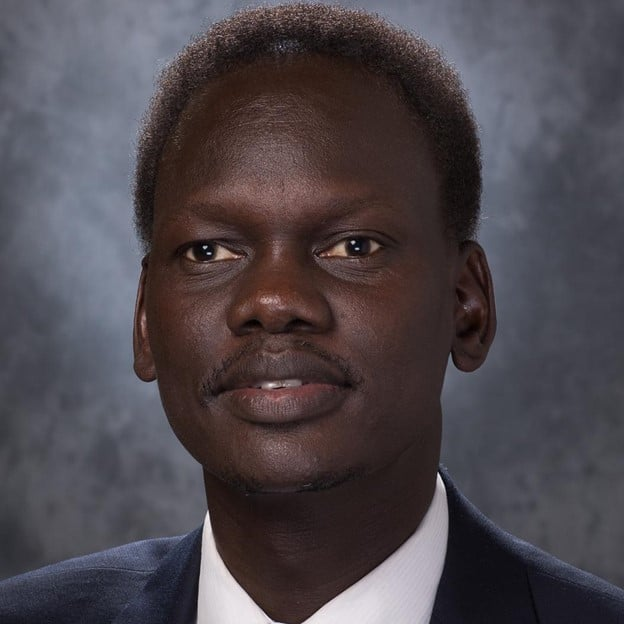

Deng Majok Chol is one of the Red Army veterans that SPLM/A planted as seeds of the nation who later moved to the U.S to further his education.

According to Deng, he is who he is now because of Dr. John Garang’s revolutionary vision he and his comrade made nearly 40 years ago.

But who is Deng Majok Chol?

Before the controversies on the Nile waters emerged early this year, Majok was not known to many.

However, during the recently concluded public consultation and awareness on the Sudd wetlands, he became one of the most notable voices demanding a scientific approach to the failed government project seeking to dredge some tributaries of the Nile.

He is currently among the most educated people in the country, having graduated from Harvard and Oxford; two of the world’s most prestigious universities.

Born to a former Head Chief of Dinka-Nyarweng in Poktap of Duk County, Majok suffered the storms of the civil war as a little boy, before he found his way to the United States.

Deng and three of his siblings were born in Duk County in Jonglei state in the 1970s and 1980s.

His mother, Adhieu Alaak Pageer, was the bedrock of the family. She cultivates three farms where she grows millets. Two family farms were closer to the homestead and the other far away.

In his childhood, Deng was prepared to be a successful person and future chief in his village before the Sudan civil war turned his world upside down.

“I was prepared to be a successful person in that, to be part and parcel of the village and perhaps to be the future chief in the area.”

According to Deng, he is who he is now because of Dr. John Garang’s revolutionary vision he made nearly 40 years ago.

“I was trained in great values of a family, hospitality, welcoming the guests, hardworking, and honesty.”

“I was prepared as a responsible Dinka man who can take care of cattle, find a way to raise cattle and save cattle and get more cattle.”

The unbearable bushes

In 1987, at the age of ten, Deng left his village with several unaccompanied children after the second Sudan civil war that broke out in 1983.

Deng was told by his father that he and other children were heading to the bush to get an education.

“I couldn’t imagine what it means to be in the bush.”

He vividly remembered how Sudanese high-altitude, the Russian-made Anitnop plane dropped several bombs on them in Mach Deng village not far from Bor town.

This is where he first saw Capt. Kuol Manyang Juk, the then commander of SPLA forces in the area, and who gave the first introduction speech to Deng and other children about bush life and the struggle ahead of them.

Deng with other children proceeded to Pibor where they walked for more than seven days before reaching Pibor, where they lost one of their comrades due to dehydration and thirst.

The journey from Pibor to Ethiopia via Pochala took them several weeks which was exhausting as they were starving after they ran out of water and food they carried with them.

After arriving in Ethiopia’s Pugnido (Pinyido) refugee camp, over 30, 000 children including Deng were received by some SPLA fighters, who directed them to settle under trees without sleeping materials, and food.

In the camp, the unaccompanied children as they used to be called were divided into smaller groups.

Deng and his comrades were picked from different parts of Sudan, especially South Sudan: Upper Nile, Bahr el Ghazal, and Equatoria

Although the minors were now safe from aerial bombardment of the Sudanese army in the camp, diseases and inadequate food hit them hard in the camp and the suffering was unimaginable.

Deng said that a good number of young boys died from treatable diseases such as diarrhea, measles, typhoid, chickenpox, and hepatitis.

“I remembered spending time next to the hospital with visiting relatives from the Twic side. For the whole day, people were carrying dead bodies to the graveyard, and that traumatized me that day. It took me a long time to come back.” said Deng.

The issue of food at the beginning was very limited in the camp, according to Deng.

“We began with one tractor. One tractor would come from Gambella and it only comes once a week.”

Due to lack of food, minors were malnourished in the camp. As a result, there were those whose knees were now bent inward and those whose knees were stretched outward (bow legs).

Deng remembered that the military orientation by SPLA began in the camp after minors were regrouped in the military style they used to call ‘mixing or integration’.

The boys were mobilized from their villages through the Head Chiefs of various tribes or clans by zonal commanders including then Commander Riek Machar Teny, Commander Awet AKot, Commander James Wani Igga, Commander Yusep Kwa Mekka, Commander Kuol Manyang Juuk, among others.

According to Deng, the SPLA fighters would bring boys from Nuer, Dinka, Equatoria, and other tribes into the smallest unit- squad- which was about 15 young boys.

“I was the first to mix with a group of people that I never met before or know so we came together with about 15 boys.”

“We were lined up in a parade and two leaders were appointed, Wakil Arif [Lance corporal] and Arif [corporal].” Deng said.

In this small unit of group that operated like a family, some boys would go fetch firewood, others would be sent to get water, while some would go to grind the corn to turn it into flour.

This was the first time Deng was asked to pound the maize to produce maize flour.

“I was picked by Arif [corporal] to be the first one to grind the corn. But, I told him that I don’t know how to do it.”

“When I was in Duk, I was never used to it, I was always with my mother and Aunties,” Deng said.

Deng was immediately considered stubborn. And the group leader [lance corporal] formed a disciplinary committee with members who were armed with whips to make sure he did the work.

Deng was left with no option but to grind the corn and cook the food on their first day.

When Deng joined the Red Army at 13, he experienced significant trauma and hardship as a child soldier.

In 1991, Deng and his comrades in Pugnido (Pinyido) received the news that afternoon at 4 pm that the Ethiopian regime had been overthrown and the soldiers [rebels] were killing the refugees.

Deng and his colleagues had to leave the camp and carry what they could as the news came as there was no time to take everything.

“We gathered whatever little we have, some beans, wheat, and corn. we just put anything we can find. so we had to leave.”

In a matter of one hour, Deng and his comrades found themselves tracking back to Sudan (now South Sudan) the whole night with a downpour of rain under the cover of darkness.

After crossing the Gilo river, the Khartoum government immediately intercepted their arrival and resumed heavy bombardment on them.

The Red Army was met with rough conditions, wet weather, and severe hunger.

“Life in Pochalla was very rough and it was raining heavily, and with the rain came mosquitos, then hunger, and cold, all of these converged as one, and we went through the horrible experiences.”

“I remember, there was nothing to be distributed, no corn or bean, people would just go to the jungle to look for wild fruits that were edible.”

“We would identify some of the local wild fruits and eat them right there in the jungle.”

“Some people identify some wild vegetables, and we would take leaves from these plants.”

But, quite interestingly, the opposite happened. Things dramatically changed immediately, the season changed, and autumn came.

All of sudden, the river became full of fish, animal migration happened, and hunting started. Then came the UN that started food air-drop.

But unfortunately, the Red Army couldn’t enjoy the feast in Pochala.

The news came that the forces of the new government in Ethiopia were coming to attack Pochala together with the Sudanese army.

Deng and his comrades abandoned Pochala and track on foot to Kapoeta town toward the direction of the Kenya border after they were terrorized by aerial bombardments carryout by the Khartoum regime.

It took several weeks for Deng and his comrades to reach Kapoeta town after passing through many towns.

The young boys took refuge in Narus town near the Kenyan border.

After the Sudanese army dislodged SPLA forces from Kapoeta town, the young boys had to abandon Narus town overnight and entered the Kenyan border town – Lokichoggio in the morning.

Some of the teachers who were providing guidance to the boys during the Journey included Mechak Ajang Alaak, and Mayen Ngor Atem.

Deng said they were met on the way by Commander Salva Kiir Mayardit, the current President of the Republic of South Sudan, who gave the boy some water in the tanks and encouraged them to keep moving.

Deng and his colleagues were relocated to Kakuma refugee camp from Lokichoggio town where they temporarily stayed.

In Kakuma camp, the boys were met with harsh weather.

“There was Kakuma town, but the place that would become a refugee camp was just trees and dust. We were welcomed by brown dust.”

“There was an organization from Pugnido (Pinyido) that I traveled with. We were now in different groups.”

“When we arrived in Kakuma, they would say, group one, this is where you belong, and so on, and divided the camp into Zones. They make it from Zone one up to Zone 4.”

With this difficult journey, Deng still remembers a couple of leaders who he described as important leaders who helped transform the lives of the them (boys) during their long and difficult times.

Commander Ageer Gum

Deng said he was inspired by many young soldiers and several leaders of the SPLA/M movement including late Commander Ageer Gum.

Commander Taban Deng Gai and Commander James Hoth Mai

He opted admired stories of the leadership of Commander Taban Deng Gai as Chairman of the Itang Camp, Commander James Hoth Mai as Chairman of the Dima Camp.

Deng Dau Malek and Maker Thiong Maal

Deng said he has close interactions with Deng Dau Malek who was chairman of Kakuma Camp, and Ustas, as well as Maker Thiong Maal, who was the Director of Education in Camp.

Commander Pieng Deng Majok

Deng said Commander Pieng Deng Majok was one of those few leaders who he still celebrates today.

Pieng Deng Majok took after Deng Garang Beny as the Chairman of the Pugnido (Pinyido) Refugee Camp, along with Captain Paul Ring.

“I remember him [Pieng] as a great leader. He would travel across the boys checking on us, and sometimes sitting with us, eating whatever we were eating.”

Deng still remembers Pieng as a man of action, and a man of humility.

He added that Pieng, as a leader, used to bring himself so close to them so that he could relate to the kind of food they were eating.

General Pieng has been active in the SPLA since its inception in 1983.

Ustas Mayen Ngor Atem

Ustas Mayen Ngor Atem is another important person Deng still remembers during his difficult time as an unaccompanied child in Pugnido (Pinyido)

As someone who studied Agriculture at the University of Alexandra in Egypt, Deng said Ustas Mayen came to their aid when they were suffering from Malnutrition in the Pugnido (Pinyido) camp.

“He [Ustas Mayen] realized that we were suffering from Malnutrition and what he did, he went along the bank of the Pugnido (Pinyido) river and did a survey.”

“He brought us together as boys, he is well known for his famous way of saying by opening his hands and would say: “min hine le hine” [from here up to there] is a plenty of food Jiech el hamer.”

Ustas Mayen was able to mobilize the Red Army as human capital with all the tools he could get from the UN to cultivate their own food.

Through Mayen’s initiative, the boys were now able to eat a balanced diet after growing their own vegetables such as okra, tomatoes, and cabbage which helped fight Malnutrition among the boys.

“If you mention Ustas Mayen Ngor Atem to lost boys, they will just remember “Min Hine Le Hine, plenty of food.”

Isaac Mabor Teny

There came an episode where Dr. John Garang was visiting the camp for the first time.

According to Deng, there was huge preparation that was going on in the camp and Deng was very curious why this was becoming a big deal.

One of the teachers in the camp named Isaac Mabor Teny was very close to Deng, and he went to find out from him.

Ustas Isaac told Deng that the preparation is happening because the top leadership of SPLM/A is visiting the camp, and that the founder and the Chairman of the movement is coming.

But, Deng insisted on why it was such a big deal, and Isaac told him that the man is a leader and a very educated man.

“I said how educated he is, and he said he has a doctorate. So I and Ustas Mabor went back and forth over this and I couldn’t imagine what a PhD is… but Isaac kept telling me Dr. John has completed education.”

A few days later, Dr. John arrived in Pugnido (Pinyido) camp.

Dr. John Garang

In 1989, Dr. John Garang de Mabior visited the Pugnido (Pinyido) refugee camp for the first time, according to Deng.

Deng said he remembered what Dr. John told them during the parade, and according to Deng, this was mind-boggling.

“I remembered one thing he said. He told us this revolution is a long struggle. If you boys aren’t impatient, continue with your education.”

“Everyone will have a chance to fight, even your own children will fight this revolution.”

“This was mind-boggling, that of my own child, and here I was at the age of 12, and Dr. Jong Garang is telling me that my own child will fight this revolutionary war.”

Nearly 40 years after Dr. John Garang made the statement in Pugnido (Pinyido), Deng believed that what the revolutionary Garang and his generation means goes beyond the independence of South Sudan.

He stated that Garang’s never-ending revolutionary war remarks mean that all of us must fight the illiteracy’s war in South Sudan.

“I think that visionary statement from Dr. John, one could go further and say that for a nation to be completely independent.”

“It has to be able to shutter its own direction, its own direction as related to nation building, to the rule of law, to economic independence.”

“How it positions itself in the geopolitics, with the rest of the world, within the international community, that such a nation will also to realize that for us to be South Sudanese, and to first and foremost South Sudanese,

“We have to do a major task, and its major task that all these 64 ethnic groups will have to first and formal look at each other as South Sudanese as citizens of one country before they are member respected tribe, before one region or the others, so I think my children can also fight the war of illiteracy.

Deng is advising young people not to lose hope in life.

He stated that when he began his education in Pugnido (Pinyido) camp in Ethiopia at the age of 13, he was absolutely illiterate, and his first classroom was in a shade of a tree.

“When I first began in Pugnido (Pinyido) refugee camp at the age of 13, I was completely illiterate. I don’t know how to write in Dinka or English.”

“The tree was my classroom. The sandy soil was my notebook. I had to use my index finger as my pencil,

“I used my feet as my eraser – what we call rubber. That is how my education began and here I am today.”

Later on, during the journey from Ethiopia to Sudan and then to Kenya, he self-educated himself with English vocabulary whenever he found breaks by reading two Bible texts, one on Dinka and the other in the English Language.

By reading verse by verse, paragraph by paragraph, sentence by sentence in both languages, he was able to discern the meaning of the English words, that he wrote down it what would become known as the “hand-written dictionary” among the red Army.

Deng said he is where he is today due to a lot of struggle.

He said he first wore his first shoe when he was a senior-one or form-one in Kenya.

“I am where I am today because of a lot of struggle. In Kakuma, I never wore any shoes until I was sponsored after I finished my eighth grade, what was called KCPE and did well, and I was sponsored by Jesuit Refugee Service – JRS.”

“When JRS came and sponsored me to a high school St. Leo in Turkana District, that is when I first got my shoe, to put one on in secondary school.”

Deng challenged young people that they need to be strong as they struggle and it’s when you struggle when windows open, and when God mercy reigns.

The Harvard graduate thanked the generation of Dr. John Garang, President Salva Kiir, Dr. Riek Machar, Dr. Wani Igga, and late Commander Yusep Kwa Mekka for liberating South Sudanese.

He added that it was because of the struggle of the people of South Sudan that he was able to go to the United States of America where he was educated.

Deng also played his part in the Sudan Peace Advocacy in the US. He helped mobilize the Lost Boys in the US and organized them into several chapters, which then engaged the US Congress at the district or state level.

From 2001 to 2005, Deng was command on Capitol Hill along with his colleagues from the red army educating American Policy Makers to understand the war in the Sudan.

The over goal of the advocacy work was to get Washington President George W. Bush to help broker the Peace in the Sudan and to end the suffering of the people.

Deng was the first lost boy to graduate from US university in 2004.

Deng and his group including the current Aweil Bishop Abraham Yel Nhial challenged the White House, and UN, about why they never intervened in the Sudan war that had caused 2.5 million lives and had taken over two decades.

Deng was asked to represent South Sudanese in the US in the 2008 SPLM 2nd Convention in Juba, South Sudan.

This was the first time he made it back to the country since his plight in Narus to Kakuma in 1992.

As luck would have been it, Deng was on the fieldwork with the World Bank in Juba in 2011 when he participated in the jubilant celebration of the Independence of the Republic of South Sudan.

Early in the morning of July 9th, he joined the US delegation including late General Colin Powell to graduate US Consular by cutting the ribbon to U.S Embassy.

In 2013, Deng was called by Obama Administration to translate President Obama’s statement in in local languages and be aired in local radio radios in South Sudan.

Deng is a strong supporter of the Republic of South Sudan, and the Government.

He wants to use his knowledge to advance the country in the areas of water resources management and the socio-economic transformation of the country.

Deng believes that the relationship between the US and South Sudan can be revived if the right people understand how the American interest to broker the Comprehensive Peace Agreement (CPA) in 2005.

Deng is now a holder of several degrees and a Ph.D. student in Oxford in the United Kingdom.

He earned a B.S. in political science and Economics from Arizona State, a two-year MBA from George Washington University, and a two-year MPA from Harvard University.

Deng is a researcher in the Abdul Latif Jameel Water and Food Systems Laboratory (J-WAFS) at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT).

He is also a researcher for the United Nations Office for Project Services (UNOPS) in partnership with Oxford University.

Deng is also a researcher on the Ghana Infrastructure Project that uses the National Infrastructure Systems Model (NISMO), which was used for the UK’s first National Infrastructure Assessment and analysis of the resilience of energy, transport, digital, and water networks in Great Britain.

Previously he was a project assistant at the Center for Global Change Science (CGCS) at MIT.

He is currently a DPhil Candidate at Oxford University pursuing research on the socio Eco-hydrology of South Sudan under climate and socio-economic change: South Sudan’s lungs: sustaining the Sudd under climate and socio-economic change.

His DPhil study covers these research areas: The Nile water resources, climate change hydrodynamics, environmental risks, hydrological modelling, climatic and variability simulations, and socio-economic, and regional climate models.

His study goal is to produce a sustainable development plan for South Sudan that must address the issues of a seasonally flooded population of the Sudd and include actions to reduce the risks of flood damage to allow for the construction of infrastructure to enhance social welfare and sustainable economic development while preserving the ecosystem services and intrinsic value of the Sudd.

He has extensive experience with the management of other major river basins around the world: The Okavango Delta, Zambezi, Congo, and Colorado.

In 2014 he had an independent project on Peace and Reconciliation of South Sudan as part of his Harvard Summer Internship.